Why Batteries Break Traditional Simulation Workflows

Why Batteries Break Traditional Simulation Workflows

Simulation has transformed nearly every engineering discipline. It took aerospace from physical wind tunnel testing to computational fluid dynamics. It moved architecture from drafting tables to computer-aided engineering. It enabled the semiconductor industry to design chips with billions of transistors without fabricating each iteration. In each of these fields, simulation compressed development cycles from months or years down to days, changing how engineers work.

Batteries haven't had that moment yet. Despite decades of investment in modeling tools and growing urgency to accelerate development timelines, battery engineering is still dominated by build-test-iterate cycles. Teams spend months fabricating cells, running tests, analyzing results, and making incremental adjustments, often to discover that the design they converged on doesn't hold up when operating conditions or requirements change. The simulation tools that revolutionized other engineering fields haven't delivered the same step change for batteries. Not because the software isn't fast enough or the computers aren't powerful enough, but because the fundamental nature of the problem is different.

Why battery modeling is different

In most engineering simulation, the physics is well understood and the challenge comes from scaling up the geometry. If you're designing a skyscraper, you know the shear modulus of the steel beams and the compressive strength of the concrete. The hard part is meshing a complex 3D structure and solving the equations efficiently across that geometry. The same is true in aerodynamics: the material properties of air are well characterized, and the difficulty lies in resolving turbulent flow around intricate shapes.

Traditional CAD-based simulation tools were built for this kind of problem. You input your material properties (often looked up from a database), input your design as a CAD file, and the solver gives you the result. Companies like ANSYS and COMSOL have been enormously successful applying this approach to structural mechanics, fluid dynamics, and electromagnetics.

Naturally, the same companies have tried to apply this approach to batteries. It hasn't worked particularly well. The reason is that in batteries, the geometry is actually pretty simple. A cell is essentially a stack of thin layers. The hard part is the physics and the parameters.

In this sense, batteries are much closer to living organisms than they are to physical infrastructure. The behavior of a battery depends on a web of interdependent properties that are difficult to measure, difficult to decouple, and often change depending on context. A few examples:

Interfacial properties depend on the combination of materials, not just the materials themselves. The intercalation reaction rate at an NMC cathode surface depends on which electrolyte it's paired with, what additives are present, and even how the electrode was processed. You can't just look this up in a table.

Properties change their meaning at different scales. You can measure lithium diffusivity in a single particle using techniques like GITT, but the cell-scale model typically assumes spherical particles, which changes what "diffusion coefficient" actually refers to. The model parameter is no longer the fundamental material property. It's an effective parameter that absorbs the complexity of the real microstructure.

Properties change after building the battery. Electrolyte properties measured in a pristine solution can shift meaningfully after formation, as the initial SEI layer grows and some electrolyte is consumed.

Models are themselves approximations of complex phenomena. When we talk about "the SEI growth rate," we're referring to a single modeled reaction. In reality, SEI forms through dozens of competing reactions at the anode-electrolyte interface, each with its own kinetics and products. The model lumps all of this into one effective parameter.

Should we give up on physics and just use AI?

This is a question we get a lot. If the parameters are so uncertain and the models are approximations anyway, why not skip the physics entirely and train a machine learning model on the data?

There are a few reasons this doesn't work well at the R&D stage. First, we're typically working with relatively small datasets. A battery development team might have rate capability data at a handful of C-rates, a few temperatures, and maybe some cycle life data. That's not enough to train a general-purpose ML model that can extrapolate reliably to new conditions.

Second, individual datasets can't easily be combined or cross-examined with a single ML model. The data from a half-cell test, a rate capability test, and an EIS measurement each tell you something different about the cell, and a physics-based model provides the framework for synthesizing these different data sources into a coherent picture. A purely data-driven model would need to learn this structure from scratch, which requires far more data than is typically available.

Third, we do know some physics. Conservation of mass tells us that all of the lithium in the battery has to go somewhere: mostly shuttling back and forth between the electrodes, but sometimes going into side reactions like SEI growth or lithium plating. These constraints are extremely powerful and shouldn't be thrown away.

That said, AI does show real promise at the material level, where large datasets from high-throughput experimentation or DFT calculations are more readily available. The right approach isn't physics or AI but rather physics and AI, using physical models as the backbone and data-driven methods to fill in the gaps.

Introducing the Simulation OS

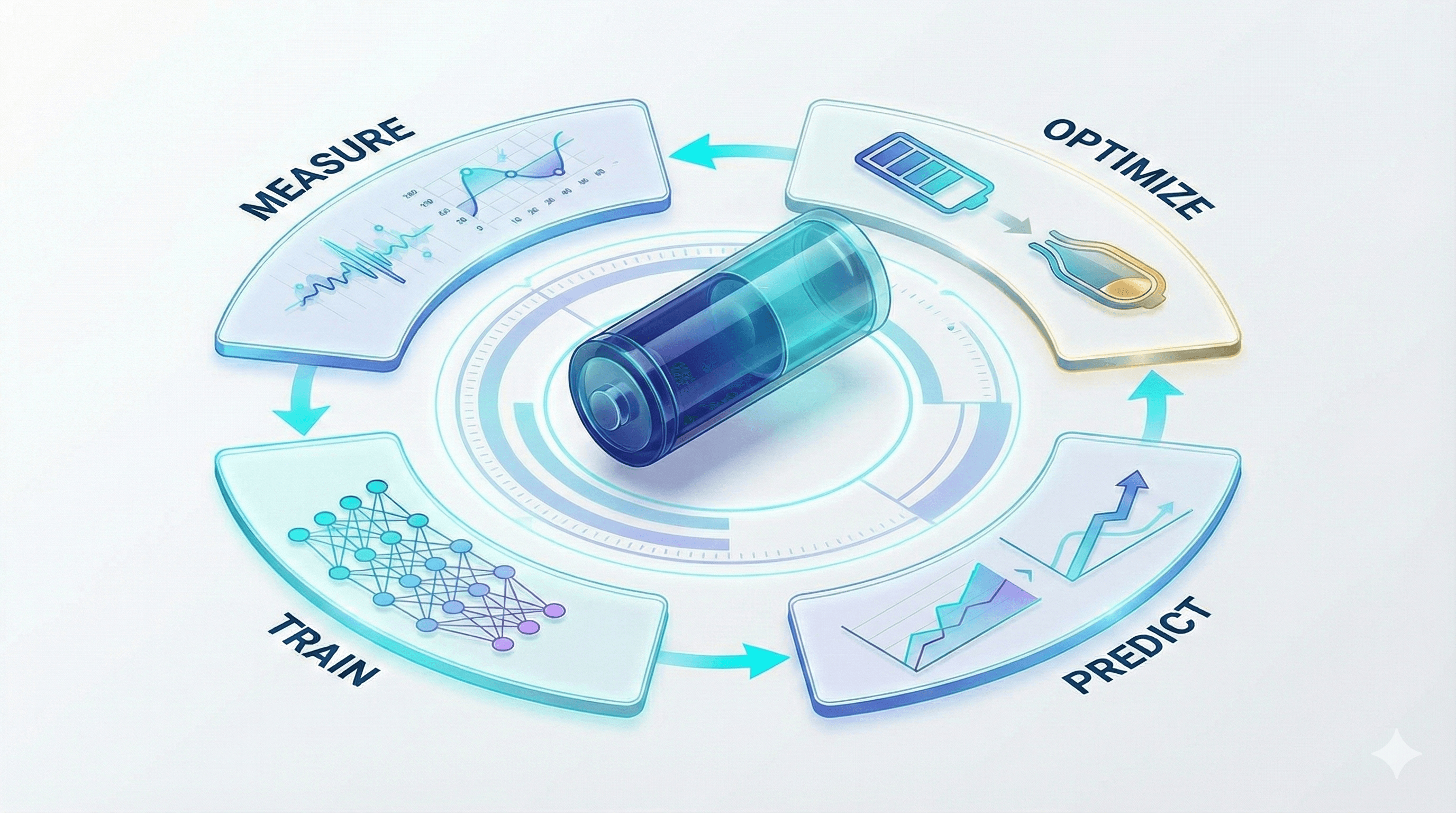

Given all of this, what does a good battery simulation workflow actually look like? We think of it as a four-step loop: measure, train, predict, optimize.

Measure

Every battery simulation effort starts with data. At a minimum, this includes testing data on the full cell itself: rate capability tests at different C-rates and temperatures, perhaps some drive cycles or other application-relevant profiles. Sometimes it includes more advanced characterization: half-cell testing to separate cathode and anode contributions, EIS for impedance characterization, or direct measurement of internal properties like electrode thickness and porosity.

The Simulation OS provides a system of record for this data. It harmonizes, stores, visualizes, and provides programmatic access to battery R&D data in a standardized format, making it easy to keep track of different cell tests alongside the metadata of the cell that was tested (chemistry, format, electrode specifications, electrolyte composition, manufacturing parameters like press density and formation protocol, and so on).

Train

Using the data you've collected, the next step is to identify the parameters that can't be directly measured. Within the battery modeling community, this step is more commonly called "parameterization," but it's conceptually equivalent to model training in machine learning. You have a physics-based model with some known parameters and some unknown ones, and you fit the unknowns to your experimental data.

Just like in classical ML, you use train/test splits to validate that the model generalizes. You might fit the model to rate capability data and then check whether it accurately predicts a drive cycle that wasn't used in training.

Predict

Once you have a parameterized model, you can use it to explore scenarios that would be expensive or time-consuming to test experimentally. This is where simulation really starts to pay off.

You can predict how changing electrode thickness or press density will affect the tradeoff between energy density and power capability. You can simulate a fast-charge protocol and track internal variables that are hard or impossible to measure directly: anode potential (to assess lithium plating risk), core temperature, or mechanical stress in the active material particles. You can evaluate how different formation protocols affect initial capacity loss and SEI stability. You can project degradation pathways under the same operating conditions, or predict how degradation will differ under a completely new duty cycle.

These are questions that would otherwise require weeks or months of testing to answer experimentally. But prediction alone still requires a lot of manual trial and error. You're asking "if I change X, what happens to Y?" and then iterating: trying different electrode thicknesses, different press densities, different charge profiles, and checking the results each time. It's faster than running the experiments, but you're still searching through the design space by hand.

Optimize

Optimization flips the script. Instead of starting with a design and predicting its performance, you start with the target performance and let the system find the best design.

Instead of "if I add 5% silicon, what is the effect on energy density and swelling?", you ask "what silicon content will give me 350 Wh/kg and no more than 10% electrode expansion?" Instead of manually sweeping through formation protocols, you ask "which formation protocol maximizes coulombic efficiency while minimizing first-cycle capacity loss?" Instead of guessing at charge profiles, you ask "what is the fastest charge rate that avoids lithium plating across the full temperature range?"

This extends naturally to manufacturing parameters too. Rather than running dozens of simulations at different press densities and coating thicknesses, you specify your energy density target and cycle life requirement and let the optimizer find the combination of manufacturing parameters that gets you there.

This mode is particularly powerful because it lets engineers specify what they want and lets the model figure out how to get there. It turns simulation from a tool for checking ideas into a tool for generating them.

The loop

It's common for the first pass through these four steps to not give perfect results. The model might not be accurate in the new operating conditions suggested by the optimizer, or you might enter a regime where a new constraint becomes important that wasn't considered initially (for example, surface temperature limits during fast charging).

This is fine, and expected. You just repeat the loop: collect new data in the regions where the model was inaccurate, add any new constraints you've identified, and retrain. The model learns to fit the newly available data, and your predictions get more reliable with each iteration.

This iterative process is very different from the traditional CAD simulation workflow of "set up the model, click solve, get the answer." It's closer to how ML practitioners think about model development: an ongoing cycle of data collection, training, validation, and refinement. The difference is that the underlying model encodes physics rather than being a black box, which means it generalizes better with less data and produces results that are interpretable and trustworthy.

At Ionworks, we call this workflow the Simulation OS. To find out more, book a demo or get in touch.

Simulation has transformed nearly every engineering discipline. It took aerospace from physical wind tunnel testing to computational fluid dynamics. It moved architecture from drafting tables to computer-aided engineering. It enabled the semiconductor industry to design chips with billions of transistors without fabricating each iteration. In each of these fields, simulation compressed development cycles from months or years down to days, changing how engineers work.

Batteries haven't had that moment yet. Despite decades of investment in modeling tools and growing urgency to accelerate development timelines, battery engineering is still dominated by build-test-iterate cycles. Teams spend months fabricating cells, running tests, analyzing results, and making incremental adjustments, often to discover that the design they converged on doesn't hold up when operating conditions or requirements change. The simulation tools that revolutionized other engineering fields haven't delivered the same step change for batteries. Not because the software isn't fast enough or the computers aren't powerful enough, but because the fundamental nature of the problem is different.

Why battery modeling is different

In most engineering simulation, the physics is well understood and the challenge comes from scaling up the geometry. If you're designing a skyscraper, you know the shear modulus of the steel beams and the compressive strength of the concrete. The hard part is meshing a complex 3D structure and solving the equations efficiently across that geometry. The same is true in aerodynamics: the material properties of air are well characterized, and the difficulty lies in resolving turbulent flow around intricate shapes.

Traditional CAD-based simulation tools were built for this kind of problem. You input your material properties (often looked up from a database), input your design as a CAD file, and the solver gives you the result. Companies like ANSYS and COMSOL have been enormously successful applying this approach to structural mechanics, fluid dynamics, and electromagnetics.

Naturally, the same companies have tried to apply this approach to batteries. It hasn't worked particularly well. The reason is that in batteries, the geometry is actually pretty simple. A cell is essentially a stack of thin layers. The hard part is the physics and the parameters.

In this sense, batteries are much closer to living organisms than they are to physical infrastructure. The behavior of a battery depends on a web of interdependent properties that are difficult to measure, difficult to decouple, and often change depending on context. A few examples:

Interfacial properties depend on the combination of materials, not just the materials themselves. The intercalation reaction rate at an NMC cathode surface depends on which electrolyte it's paired with, what additives are present, and even how the electrode was processed. You can't just look this up in a table.

Properties change their meaning at different scales. You can measure lithium diffusivity in a single particle using techniques like GITT, but the cell-scale model typically assumes spherical particles, which changes what "diffusion coefficient" actually refers to. The model parameter is no longer the fundamental material property. It's an effective parameter that absorbs the complexity of the real microstructure.

Properties change after building the battery. Electrolyte properties measured in a pristine solution can shift meaningfully after formation, as the initial SEI layer grows and some electrolyte is consumed.

Models are themselves approximations of complex phenomena. When we talk about "the SEI growth rate," we're referring to a single modeled reaction. In reality, SEI forms through dozens of competing reactions at the anode-electrolyte interface, each with its own kinetics and products. The model lumps all of this into one effective parameter.

Should we give up on physics and just use AI?

This is a question we get a lot. If the parameters are so uncertain and the models are approximations anyway, why not skip the physics entirely and train a machine learning model on the data?

There are a few reasons this doesn't work well at the R&D stage. First, we're typically working with relatively small datasets. A battery development team might have rate capability data at a handful of C-rates, a few temperatures, and maybe some cycle life data. That's not enough to train a general-purpose ML model that can extrapolate reliably to new conditions.

Second, individual datasets can't easily be combined or cross-examined with a single ML model. The data from a half-cell test, a rate capability test, and an EIS measurement each tell you something different about the cell, and a physics-based model provides the framework for synthesizing these different data sources into a coherent picture. A purely data-driven model would need to learn this structure from scratch, which requires far more data than is typically available.

Third, we do know some physics. Conservation of mass tells us that all of the lithium in the battery has to go somewhere: mostly shuttling back and forth between the electrodes, but sometimes going into side reactions like SEI growth or lithium plating. These constraints are extremely powerful and shouldn't be thrown away.

That said, AI does show real promise at the material level, where large datasets from high-throughput experimentation or DFT calculations are more readily available. The right approach isn't physics or AI but rather physics and AI, using physical models as the backbone and data-driven methods to fill in the gaps.

Introducing the Simulation OS

Given all of this, what does a good battery simulation workflow actually look like? We think of it as a four-step loop: measure, train, predict, optimize.

Measure

Every battery simulation effort starts with data. At a minimum, this includes testing data on the full cell itself: rate capability tests at different C-rates and temperatures, perhaps some drive cycles or other application-relevant profiles. Sometimes it includes more advanced characterization: half-cell testing to separate cathode and anode contributions, EIS for impedance characterization, or direct measurement of internal properties like electrode thickness and porosity.

The Simulation OS provides a system of record for this data. It harmonizes, stores, visualizes, and provides programmatic access to battery R&D data in a standardized format, making it easy to keep track of different cell tests alongside the metadata of the cell that was tested (chemistry, format, electrode specifications, electrolyte composition, manufacturing parameters like press density and formation protocol, and so on).

Train

Using the data you've collected, the next step is to identify the parameters that can't be directly measured. Within the battery modeling community, this step is more commonly called "parameterization," but it's conceptually equivalent to model training in machine learning. You have a physics-based model with some known parameters and some unknown ones, and you fit the unknowns to your experimental data.

Just like in classical ML, you use train/test splits to validate that the model generalizes. You might fit the model to rate capability data and then check whether it accurately predicts a drive cycle that wasn't used in training.

Predict

Once you have a parameterized model, you can use it to explore scenarios that would be expensive or time-consuming to test experimentally. This is where simulation really starts to pay off.

You can predict how changing electrode thickness or press density will affect the tradeoff between energy density and power capability. You can simulate a fast-charge protocol and track internal variables that are hard or impossible to measure directly: anode potential (to assess lithium plating risk), core temperature, or mechanical stress in the active material particles. You can evaluate how different formation protocols affect initial capacity loss and SEI stability. You can project degradation pathways under the same operating conditions, or predict how degradation will differ under a completely new duty cycle.

These are questions that would otherwise require weeks or months of testing to answer experimentally. But prediction alone still requires a lot of manual trial and error. You're asking "if I change X, what happens to Y?" and then iterating: trying different electrode thicknesses, different press densities, different charge profiles, and checking the results each time. It's faster than running the experiments, but you're still searching through the design space by hand.

Optimize

Optimization flips the script. Instead of starting with a design and predicting its performance, you start with the target performance and let the system find the best design.

Instead of "if I add 5% silicon, what is the effect on energy density and swelling?", you ask "what silicon content will give me 350 Wh/kg and no more than 10% electrode expansion?" Instead of manually sweeping through formation protocols, you ask "which formation protocol maximizes coulombic efficiency while minimizing first-cycle capacity loss?" Instead of guessing at charge profiles, you ask "what is the fastest charge rate that avoids lithium plating across the full temperature range?"

This extends naturally to manufacturing parameters too. Rather than running dozens of simulations at different press densities and coating thicknesses, you specify your energy density target and cycle life requirement and let the optimizer find the combination of manufacturing parameters that gets you there.

This mode is particularly powerful because it lets engineers specify what they want and lets the model figure out how to get there. It turns simulation from a tool for checking ideas into a tool for generating them.

The loop

It's common for the first pass through these four steps to not give perfect results. The model might not be accurate in the new operating conditions suggested by the optimizer, or you might enter a regime where a new constraint becomes important that wasn't considered initially (for example, surface temperature limits during fast charging).

This is fine, and expected. You just repeat the loop: collect new data in the regions where the model was inaccurate, add any new constraints you've identified, and retrain. The model learns to fit the newly available data, and your predictions get more reliable with each iteration.

This iterative process is very different from the traditional CAD simulation workflow of "set up the model, click solve, get the answer." It's closer to how ML practitioners think about model development: an ongoing cycle of data collection, training, validation, and refinement. The difference is that the underlying model encodes physics rather than being a black box, which means it generalizes better with less data and produces results that are interpretable and trustworthy.

At Ionworks, we call this workflow the Simulation OS. To find out more, book a demo or get in touch.

Simulation has transformed nearly every engineering discipline. It took aerospace from physical wind tunnel testing to computational fluid dynamics. It moved architecture from drafting tables to computer-aided engineering. It enabled the semiconductor industry to design chips with billions of transistors without fabricating each iteration. In each of these fields, simulation compressed development cycles from months or years down to days, changing how engineers work.

Batteries haven't had that moment yet. Despite decades of investment in modeling tools and growing urgency to accelerate development timelines, battery engineering is still dominated by build-test-iterate cycles. Teams spend months fabricating cells, running tests, analyzing results, and making incremental adjustments, often to discover that the design they converged on doesn't hold up when operating conditions or requirements change. The simulation tools that revolutionized other engineering fields haven't delivered the same step change for batteries. Not because the software isn't fast enough or the computers aren't powerful enough, but because the fundamental nature of the problem is different.

Why battery modeling is different

In most engineering simulation, the physics is well understood and the challenge comes from scaling up the geometry. If you're designing a skyscraper, you know the shear modulus of the steel beams and the compressive strength of the concrete. The hard part is meshing a complex 3D structure and solving the equations efficiently across that geometry. The same is true in aerodynamics: the material properties of air are well characterized, and the difficulty lies in resolving turbulent flow around intricate shapes.

Traditional CAD-based simulation tools were built for this kind of problem. You input your material properties (often looked up from a database), input your design as a CAD file, and the solver gives you the result. Companies like ANSYS and COMSOL have been enormously successful applying this approach to structural mechanics, fluid dynamics, and electromagnetics.

Naturally, the same companies have tried to apply this approach to batteries. It hasn't worked particularly well. The reason is that in batteries, the geometry is actually pretty simple. A cell is essentially a stack of thin layers. The hard part is the physics and the parameters.

In this sense, batteries are much closer to living organisms than they are to physical infrastructure. The behavior of a battery depends on a web of interdependent properties that are difficult to measure, difficult to decouple, and often change depending on context. A few examples:

Interfacial properties depend on the combination of materials, not just the materials themselves. The intercalation reaction rate at an NMC cathode surface depends on which electrolyte it's paired with, what additives are present, and even how the electrode was processed. You can't just look this up in a table.

Properties change their meaning at different scales. You can measure lithium diffusivity in a single particle using techniques like GITT, but the cell-scale model typically assumes spherical particles, which changes what "diffusion coefficient" actually refers to. The model parameter is no longer the fundamental material property. It's an effective parameter that absorbs the complexity of the real microstructure.

Properties change after building the battery. Electrolyte properties measured in a pristine solution can shift meaningfully after formation, as the initial SEI layer grows and some electrolyte is consumed.

Models are themselves approximations of complex phenomena. When we talk about "the SEI growth rate," we're referring to a single modeled reaction. In reality, SEI forms through dozens of competing reactions at the anode-electrolyte interface, each with its own kinetics and products. The model lumps all of this into one effective parameter.

Should we give up on physics and just use AI?

This is a question we get a lot. If the parameters are so uncertain and the models are approximations anyway, why not skip the physics entirely and train a machine learning model on the data?

There are a few reasons this doesn't work well at the R&D stage. First, we're typically working with relatively small datasets. A battery development team might have rate capability data at a handful of C-rates, a few temperatures, and maybe some cycle life data. That's not enough to train a general-purpose ML model that can extrapolate reliably to new conditions.

Second, individual datasets can't easily be combined or cross-examined with a single ML model. The data from a half-cell test, a rate capability test, and an EIS measurement each tell you something different about the cell, and a physics-based model provides the framework for synthesizing these different data sources into a coherent picture. A purely data-driven model would need to learn this structure from scratch, which requires far more data than is typically available.

Third, we do know some physics. Conservation of mass tells us that all of the lithium in the battery has to go somewhere: mostly shuttling back and forth between the electrodes, but sometimes going into side reactions like SEI growth or lithium plating. These constraints are extremely powerful and shouldn't be thrown away.

That said, AI does show real promise at the material level, where large datasets from high-throughput experimentation or DFT calculations are more readily available. The right approach isn't physics or AI but rather physics and AI, using physical models as the backbone and data-driven methods to fill in the gaps.

Introducing the Simulation OS

Given all of this, what does a good battery simulation workflow actually look like? We think of it as a four-step loop: measure, train, predict, optimize.

Measure

Every battery simulation effort starts with data. At a minimum, this includes testing data on the full cell itself: rate capability tests at different C-rates and temperatures, perhaps some drive cycles or other application-relevant profiles. Sometimes it includes more advanced characterization: half-cell testing to separate cathode and anode contributions, EIS for impedance characterization, or direct measurement of internal properties like electrode thickness and porosity.

The Simulation OS provides a system of record for this data. It harmonizes, stores, visualizes, and provides programmatic access to battery R&D data in a standardized format, making it easy to keep track of different cell tests alongside the metadata of the cell that was tested (chemistry, format, electrode specifications, electrolyte composition, manufacturing parameters like press density and formation protocol, and so on).

Train

Using the data you've collected, the next step is to identify the parameters that can't be directly measured. Within the battery modeling community, this step is more commonly called "parameterization," but it's conceptually equivalent to model training in machine learning. You have a physics-based model with some known parameters and some unknown ones, and you fit the unknowns to your experimental data.

Just like in classical ML, you use train/test splits to validate that the model generalizes. You might fit the model to rate capability data and then check whether it accurately predicts a drive cycle that wasn't used in training.

Predict

Once you have a parameterized model, you can use it to explore scenarios that would be expensive or time-consuming to test experimentally. This is where simulation really starts to pay off.

You can predict how changing electrode thickness or press density will affect the tradeoff between energy density and power capability. You can simulate a fast-charge protocol and track internal variables that are hard or impossible to measure directly: anode potential (to assess lithium plating risk), core temperature, or mechanical stress in the active material particles. You can evaluate how different formation protocols affect initial capacity loss and SEI stability. You can project degradation pathways under the same operating conditions, or predict how degradation will differ under a completely new duty cycle.

These are questions that would otherwise require weeks or months of testing to answer experimentally. But prediction alone still requires a lot of manual trial and error. You're asking "if I change X, what happens to Y?" and then iterating: trying different electrode thicknesses, different press densities, different charge profiles, and checking the results each time. It's faster than running the experiments, but you're still searching through the design space by hand.

Optimize

Optimization flips the script. Instead of starting with a design and predicting its performance, you start with the target performance and let the system find the best design.

Instead of "if I add 5% silicon, what is the effect on energy density and swelling?", you ask "what silicon content will give me 350 Wh/kg and no more than 10% electrode expansion?" Instead of manually sweeping through formation protocols, you ask "which formation protocol maximizes coulombic efficiency while minimizing first-cycle capacity loss?" Instead of guessing at charge profiles, you ask "what is the fastest charge rate that avoids lithium plating across the full temperature range?"

This extends naturally to manufacturing parameters too. Rather than running dozens of simulations at different press densities and coating thicknesses, you specify your energy density target and cycle life requirement and let the optimizer find the combination of manufacturing parameters that gets you there.

This mode is particularly powerful because it lets engineers specify what they want and lets the model figure out how to get there. It turns simulation from a tool for checking ideas into a tool for generating them.

The loop

It's common for the first pass through these four steps to not give perfect results. The model might not be accurate in the new operating conditions suggested by the optimizer, or you might enter a regime where a new constraint becomes important that wasn't considered initially (for example, surface temperature limits during fast charging).

This is fine, and expected. You just repeat the loop: collect new data in the regions where the model was inaccurate, add any new constraints you've identified, and retrain. The model learns to fit the newly available data, and your predictions get more reliable with each iteration.

This iterative process is very different from the traditional CAD simulation workflow of "set up the model, click solve, get the answer." It's closer to how ML practitioners think about model development: an ongoing cycle of data collection, training, validation, and refinement. The difference is that the underlying model encodes physics rather than being a black box, which means it generalizes better with less data and produces results that are interpretable and trustworthy.

At Ionworks, we call this workflow the Simulation OS. To find out more, book a demo or get in touch.

Simulation has transformed nearly every engineering discipline. It took aerospace from physical wind tunnel testing to computational fluid dynamics. It moved architecture from drafting tables to computer-aided engineering. It enabled the semiconductor industry to design chips with billions of transistors without fabricating each iteration. In each of these fields, simulation compressed development cycles from months or years down to days, changing how engineers work.

Batteries haven't had that moment yet. Despite decades of investment in modeling tools and growing urgency to accelerate development timelines, battery engineering is still dominated by build-test-iterate cycles. Teams spend months fabricating cells, running tests, analyzing results, and making incremental adjustments, often to discover that the design they converged on doesn't hold up when operating conditions or requirements change. The simulation tools that revolutionized other engineering fields haven't delivered the same step change for batteries. Not because the software isn't fast enough or the computers aren't powerful enough, but because the fundamental nature of the problem is different.

Why battery modeling is different

In most engineering simulation, the physics is well understood and the challenge comes from scaling up the geometry. If you're designing a skyscraper, you know the shear modulus of the steel beams and the compressive strength of the concrete. The hard part is meshing a complex 3D structure and solving the equations efficiently across that geometry. The same is true in aerodynamics: the material properties of air are well characterized, and the difficulty lies in resolving turbulent flow around intricate shapes.

Traditional CAD-based simulation tools were built for this kind of problem. You input your material properties (often looked up from a database), input your design as a CAD file, and the solver gives you the result. Companies like ANSYS and COMSOL have been enormously successful applying this approach to structural mechanics, fluid dynamics, and electromagnetics.

Naturally, the same companies have tried to apply this approach to batteries. It hasn't worked particularly well. The reason is that in batteries, the geometry is actually pretty simple. A cell is essentially a stack of thin layers. The hard part is the physics and the parameters.

In this sense, batteries are much closer to living organisms than they are to physical infrastructure. The behavior of a battery depends on a web of interdependent properties that are difficult to measure, difficult to decouple, and often change depending on context. A few examples:

Interfacial properties depend on the combination of materials, not just the materials themselves. The intercalation reaction rate at an NMC cathode surface depends on which electrolyte it's paired with, what additives are present, and even how the electrode was processed. You can't just look this up in a table.

Properties change their meaning at different scales. You can measure lithium diffusivity in a single particle using techniques like GITT, but the cell-scale model typically assumes spherical particles, which changes what "diffusion coefficient" actually refers to. The model parameter is no longer the fundamental material property. It's an effective parameter that absorbs the complexity of the real microstructure.

Properties change after building the battery. Electrolyte properties measured in a pristine solution can shift meaningfully after formation, as the initial SEI layer grows and some electrolyte is consumed.

Models are themselves approximations of complex phenomena. When we talk about "the SEI growth rate," we're referring to a single modeled reaction. In reality, SEI forms through dozens of competing reactions at the anode-electrolyte interface, each with its own kinetics and products. The model lumps all of this into one effective parameter.

Should we give up on physics and just use AI?

This is a question we get a lot. If the parameters are so uncertain and the models are approximations anyway, why not skip the physics entirely and train a machine learning model on the data?

There are a few reasons this doesn't work well at the R&D stage. First, we're typically working with relatively small datasets. A battery development team might have rate capability data at a handful of C-rates, a few temperatures, and maybe some cycle life data. That's not enough to train a general-purpose ML model that can extrapolate reliably to new conditions.

Second, individual datasets can't easily be combined or cross-examined with a single ML model. The data from a half-cell test, a rate capability test, and an EIS measurement each tell you something different about the cell, and a physics-based model provides the framework for synthesizing these different data sources into a coherent picture. A purely data-driven model would need to learn this structure from scratch, which requires far more data than is typically available.

Third, we do know some physics. Conservation of mass tells us that all of the lithium in the battery has to go somewhere: mostly shuttling back and forth between the electrodes, but sometimes going into side reactions like SEI growth or lithium plating. These constraints are extremely powerful and shouldn't be thrown away.

That said, AI does show real promise at the material level, where large datasets from high-throughput experimentation or DFT calculations are more readily available. The right approach isn't physics or AI but rather physics and AI, using physical models as the backbone and data-driven methods to fill in the gaps.

Introducing the Simulation OS

Given all of this, what does a good battery simulation workflow actually look like? We think of it as a four-step loop: measure, train, predict, optimize.

Measure

Every battery simulation effort starts with data. At a minimum, this includes testing data on the full cell itself: rate capability tests at different C-rates and temperatures, perhaps some drive cycles or other application-relevant profiles. Sometimes it includes more advanced characterization: half-cell testing to separate cathode and anode contributions, EIS for impedance characterization, or direct measurement of internal properties like electrode thickness and porosity.

The Simulation OS provides a system of record for this data. It harmonizes, stores, visualizes, and provides programmatic access to battery R&D data in a standardized format, making it easy to keep track of different cell tests alongside the metadata of the cell that was tested (chemistry, format, electrode specifications, electrolyte composition, manufacturing parameters like press density and formation protocol, and so on).

Train

Using the data you've collected, the next step is to identify the parameters that can't be directly measured. Within the battery modeling community, this step is more commonly called "parameterization," but it's conceptually equivalent to model training in machine learning. You have a physics-based model with some known parameters and some unknown ones, and you fit the unknowns to your experimental data.

Just like in classical ML, you use train/test splits to validate that the model generalizes. You might fit the model to rate capability data and then check whether it accurately predicts a drive cycle that wasn't used in training.

Predict

Once you have a parameterized model, you can use it to explore scenarios that would be expensive or time-consuming to test experimentally. This is where simulation really starts to pay off.

You can predict how changing electrode thickness or press density will affect the tradeoff between energy density and power capability. You can simulate a fast-charge protocol and track internal variables that are hard or impossible to measure directly: anode potential (to assess lithium plating risk), core temperature, or mechanical stress in the active material particles. You can evaluate how different formation protocols affect initial capacity loss and SEI stability. You can project degradation pathways under the same operating conditions, or predict how degradation will differ under a completely new duty cycle.

These are questions that would otherwise require weeks or months of testing to answer experimentally. But prediction alone still requires a lot of manual trial and error. You're asking "if I change X, what happens to Y?" and then iterating: trying different electrode thicknesses, different press densities, different charge profiles, and checking the results each time. It's faster than running the experiments, but you're still searching through the design space by hand.

Optimize

Optimization flips the script. Instead of starting with a design and predicting its performance, you start with the target performance and let the system find the best design.

Instead of "if I add 5% silicon, what is the effect on energy density and swelling?", you ask "what silicon content will give me 350 Wh/kg and no more than 10% electrode expansion?" Instead of manually sweeping through formation protocols, you ask "which formation protocol maximizes coulombic efficiency while minimizing first-cycle capacity loss?" Instead of guessing at charge profiles, you ask "what is the fastest charge rate that avoids lithium plating across the full temperature range?"

This extends naturally to manufacturing parameters too. Rather than running dozens of simulations at different press densities and coating thicknesses, you specify your energy density target and cycle life requirement and let the optimizer find the combination of manufacturing parameters that gets you there.

This mode is particularly powerful because it lets engineers specify what they want and lets the model figure out how to get there. It turns simulation from a tool for checking ideas into a tool for generating them.

The loop

It's common for the first pass through these four steps to not give perfect results. The model might not be accurate in the new operating conditions suggested by the optimizer, or you might enter a regime where a new constraint becomes important that wasn't considered initially (for example, surface temperature limits during fast charging).

This is fine, and expected. You just repeat the loop: collect new data in the regions where the model was inaccurate, add any new constraints you've identified, and retrain. The model learns to fit the newly available data, and your predictions get more reliable with each iteration.

This iterative process is very different from the traditional CAD simulation workflow of "set up the model, click solve, get the answer." It's closer to how ML practitioners think about model development: an ongoing cycle of data collection, training, validation, and refinement. The difference is that the underlying model encodes physics rather than being a black box, which means it generalizes better with less data and produces results that are interpretable and trustworthy.

At Ionworks, we call this workflow the Simulation OS. To find out more, book a demo or get in touch.

Why Batteries Break Traditional Simulation Workflows

Battery engineering is still stuck in build-test-iterate cycles. The simulation tools that transformed other industries haven't worked for batteries, because the hard part isn't the geometry. It's the physics.

Why Batteries Break Traditional Simulation Workflows

Battery engineering is still stuck in build-test-iterate cycles. The simulation tools that transformed other industries haven't worked for batteries, because the hard part isn't the geometry. It's the physics.

Why Batteries Break Traditional Simulation Workflows

Battery engineering is still stuck in build-test-iterate cycles. The simulation tools that transformed other industries haven't worked for batteries, because the hard part isn't the geometry. It's the physics.

Our Commitment to Security - Ionworks is now SOC2 compliant

Learn how we protect your simulation data and IP with end-to-end encryption, role-based access controls, and continuous monitoring.

July 9, 2025

Our Commitment to Security - Ionworks is now SOC2 compliant

Learn how we protect your simulation data and IP with end-to-end encryption, role-based access controls, and continuous monitoring.

July 9, 2025

Our Commitment to Security - Ionworks is now SOC2 compliant

Learn how we protect your simulation data and IP with end-to-end encryption, role-based access controls, and continuous monitoring.

July 9, 2025

Ionworks Appoints Liam Cooney as Founding Commercial Officer

Ionworks is pleased to announce the appointment of Liam Cooney as its Founding Commercial Officer. Liam brings a distinguished track record of leadership across the energy technology and enterprise software sectors, with nearly 20 years of experience spanning commercial strategy, customer success, and technical deployment.

May 21, 2025

Ionworks Appoints Liam Cooney as Founding Commercial Officer

Ionworks is pleased to announce the appointment of Liam Cooney as its Founding Commercial Officer. Liam brings a distinguished track record of leadership across the energy technology and enterprise software sectors, with nearly 20 years of experience spanning commercial strategy, customer success, and technical deployment.

May 21, 2025

Ionworks Appoints Liam Cooney as Founding Commercial Officer

Ionworks is pleased to announce the appointment of Liam Cooney as its Founding Commercial Officer. Liam brings a distinguished track record of leadership across the energy technology and enterprise software sectors, with nearly 20 years of experience spanning commercial strategy, customer success, and technical deployment.

May 21, 2025

Why Batteries Break Traditional Simulation Workflows

Battery engineering is still stuck in build-test-iterate cycles. The simulation tools that transformed other industries haven't worked for batteries, because the hard part isn't the geometry. It's the physics.

Our Commitment to Security - Ionworks is now SOC2 compliant

Learn how we protect your simulation data and IP with end-to-end encryption, role-based access controls, and continuous monitoring.

July 9, 2025

Run your first virtual battery test today

Simulate, iterate, and validate your cell configurations with no lab time required.

Ionworks Technologies Inc. All rights reserved.

Run your first virtual battery test today

Simulate, iterate, and validate your cell configurations with no lab time required.

Run your first virtual battery test today

Simulate, iterate, and validate your cell configurations with no lab time required.

Ionworks Technologies Inc. All rights reserved.

Run your first virtual battery test today

Simulate, iterate, and validate your cell configurations with no lab time required.

Ionworks Technologies Inc. All rights reserved.